Steak Drop

From what height would you need to drop a steak for it to be cooked when it hit the ground?

—Alex Lahey

I hope you like your steaks Pittsburgh Rare. And you may need to defrost it after you pick it up.

Things get really hot when they come back from space. This isn’t because of air friction, strictly speaking—it’s because of air compression. The air can’t move out of the way fast enough, and gets squished in front of the spaceship/meteor/steak. Compressing air heats it up.

As a rule of thumb, you start to notice compressive heating above about Mach 2 (the Concorde had heat-resistant material on the leading edge of its wings).

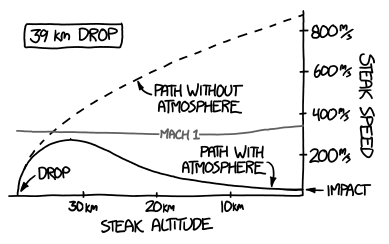

A few months ago, skydiver Felix Baumgartner jumped from 39 kilometers, and hit Mach 1 around 30 kilometers. This was enough to heat the air by a few degrees, but the air was so far below freezing that it didn’t make a difference. (Early in his jump, it was about minus 40 degrees, which is that magical point where you don’t have to clarify whether you mean Fahrenheit or Celsius—it’s the same in both.)

As far as I know, this steak question originally came up in a lengthy 4chan thread, which quickly disintegrated into poorly-informed physics tirades intermixed with homophobic slurs. There was no clear conclusion.

To try to get a better answer, I decided to run a series of simulations of a steak falling from various heights.

This involved a lot of research.

I used Mathematica models of atmospheric density to generate a set of descent profiles for the plummeting steak. For a nice tutorial on how to do this, see the Wolfram Blog’s analysis of Felix Baumgartner’s jump.

An 8 oz. steak is about the size and shape of a hockey puck, so I based my steak’s drag coefficients on those given on page 74 of The Physics of Hockey (which author Alain Haché actually measured personally using some lab equipment). A steak isn’t a hockey puck, but the precise drag coefficient turned out not to make a big difference in the result.

I used a handy NASA compressive heating calculator to determine the temperature of the shock layer in front of the steak.

Since this blog tends to wind up looking at unusual objects in extreme physical circumstances, often the only relevant research I can find is US military studies from the Cold War era. (Apparently, the US government was shoveling tons of money at anything even loosely related to weapons research.) To get an idea of how the air would heat the steak, I looked at research papers on the heating of ICBM nose cones as they reenter the atmosphere. Two of the most useful were Predictions of Aerodynamic Heating on Tactical Missile Domes and Calculation of Reentry-Vehicle Temperature History.

Lastly, I had to figure out exactly how quickly heat spreads through a steak. I started by looking at some papers from industrial food production which simulated heat flow through various pieces of meat. It took me a while to realize there was a much easier way to learn what combinations of time and temperature will effectively heat the various layers of a steak: Check a cookbook.

Jeff Potter’s excellent book Cooking for Geeks provides a great introduction to the science of cooking meat, and explains what ranges of heat produce what effects in steak and why. Cook’s The Science of Good Cooking was also helpful.

Putting it all together, I found that the steak will accelerate quickly until it reaches about an altitude of about 30-50 kilometers, at which point the air gets thick enough to start slowing it back down.

The falling steak’s speed drops steadily as the air gets thicker. No matter how fast it’s going when it reaches the lower layers of the atmosphere, it quickly slows down to terminal velocity. It always takes six or seven minutes to drop from 25 kilometers to the ground.

For much of those 25 kilometers, the air temperature is below freezing—which means the steak will spend six or seven minutes subjected to a relentless blast of subzero, hurricane-force winds. Even if it is cooked by the fall, you’ll probably have to defrost it when it lands.

When the steak does finally hit the ground, no matter the initial height, it will be traveling at about 30 meters per second. To get an idea of what this means, imagine a steak flung at the ground by a major-league pitcher. If the steak is even partially frozen, it could easily shatter. However, if it lands in the water, mud, or leaves, it will probably be fine. (Not clean, but intact.)

A steak dropped from 39 kilometers will, unlike Felix, probably not break the sound barrier. It also won’t be appreciably heated. This makes sense—after all, Felix’s suit wasn’t scorched when he landed.

Steaks can probably survive breaking the sound barrier. In addition to Felix, pilots have ejected at supersonic speeds and lived to tell about it.

To break the sound barrier, you’ll need to drop the steak from about 50 kilometers. But this isn’t enough to cook it.

We need to go higher.

If dropped from 70 kilometers, the steak will go fast enough to be briefly blasted by 350°F air. Unfortunately, this blast of thin, wispy air barely lasts a minute—and anyone with some basic kitchen experience can tell you that a steak placed in the oven at 350 for 60 seconds isn’t going to be cooked.

From 100 kilometers—the formally defined edge of space—the picture’s not much better. The steak spends a minute and a half over Mach 2, and the outer surface will likely be singed, but the heat is too quickly replaced by the icy stratospheric blast for it to actually be cooked.

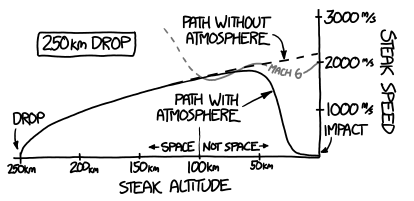

At supersonic and hypersonic speeds, a shockwave forms around the steak which helps protect it from the faster and faster winds. The exact characteristics of this shock front—and thus the mechanical stress on the steak—depend on how an uncooked 8 oz. filet tumbles at hypersonic speeds. I searched the literature, but was unable to find anything to help me estimate this.

For the sake of this simulation, I assume that at lower speeds some type of vortex shedding creates a flipping tumble, while at hypersonic speeds it’s squished into a semi-stable spheroid shape. However, this is little more than a wild guess. If anyone puts a steak in a hypersonic wind tunnel to get better data on this, please, send me the video.

If you drop the steak from 250 kilometers, things start to heat up. 250 kilometers puts us in the range of low earth orbit. However, the steak, since it’s dropped from a standstill, isn’t moving nearly as fast as an object re-entering from orbit.

The steak reaches a top speed of Mach 6, and the outer surface may even get pleasantly seared. The inside, unfortunately, is still uncooked. Unless, that is, it goes into a hypersonic tumble and explodes into chunks.

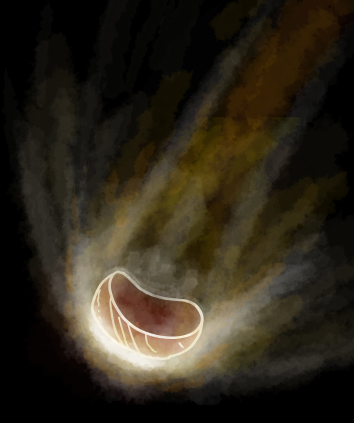

From higher altitudes, the heat starts to get really substantial. The shockwave in front of the steak reaches thousands of degrees (Fahrenheit or Celsius; it’s true in both). The problem with these levels of heat is that it burns the surface layer completely, converting it to little more than carbon. That is, it becomes charred.

Charring is a normal consequence of dropping meat in the fire. The problem with charring meat at hypersonic speeds is that the charred layer doesn’t have much structural integrity, and is blasted off by the wind—exposing a new layer to be charred. (If the heat is high enough, it will simply blast the surface layer off as it flash-cooks it. This is referred to in the ICBM papers as the “ablation zone”)

Even from those heights, the steak still doesn’t spend enough time in the heat to get cooked all the way through. (I know what some of you are probably thinking, and the answer is no—it doesn’t spend enough time in the Van Allen belts to be sterilized by radiation).

We can try higher and higher speeds, and we might lengthen the exposure time via dropping it at an angle, from orbit.

But if the temperature is high enough or the burn time long enough, the steak will slowly disintegrate as the outer layer is repeatedly charred and blasted off. If most of the steak makes it to the ground, the inside will still be raw.

Which is why we should drop the steak over Pittsburgh.

As the probably-apocryphal story goes, steel workers in Pittsburgh would cook steaks by slapping them on the glowing metal surfaces coming out of the foundry, searing the outside while leaving the inside raw. This is, supposedly, the origin of the term Pittsburgh Rare.

So drop your steak from a suborbital rocket, send out a collection team to recover it, brush it off, reheat it, cut away any badly charred sections, and dig in.

Just watch out for salmonella. And the Andromeda Strain.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário